What is a GPU? How does it work? | Explained

The story so far: In 1999, California-based Nvidia Corp. marketed a chip called GeForce 256 as “the world’s first GPU”. Its purpose was to make videogames run better and look better. In the 2.5 decades since, GPUs have moved from the discretionary world of games and visual effects to becoming part of the core infrastructure of the digital economy.

What is a GPU?

Very simply speaking, a graphics processing unit (GPU) is an extremely powerful number-cruncher.

Less simply: a GPU is a kind of computer processor built to perform many simple calculations at the same time. The more familiar central processing unit (CPU) is on the other hand built to perform a smaller number of complicated tasks quickly and to switch between tasks well.

To draw a scene on a computer screen, for instance, the computer must decide the colour of millions of pixels several times every second. A 1920 x 1080 screen has 2.07 million pixels per frame. At a frame rate of 60 per second, you will be updating more than 120 million pixels per second. Each pixel’s colour will also depend on lighting, textures, shadows, and the ‘material’ of the object.

This is an example of a task where the same steps are repeated over and over for many pixels — and GPUs are designed to do this better than CPUs.

Imagine you’re a teacher and you need to check the answer papers for an entire school. You can finish it over a few days. But if you have the help of 99 other teachers, each teacher can take a small stack and you can all wrap up in an hour. A GPU is like having hundreds or even thousands of such workers, called cores. While each core won’t be as powerful as a CPU core, the GPU has many of them and can thus complete large repetitive workloads faster.

How does a GPU do what it does?

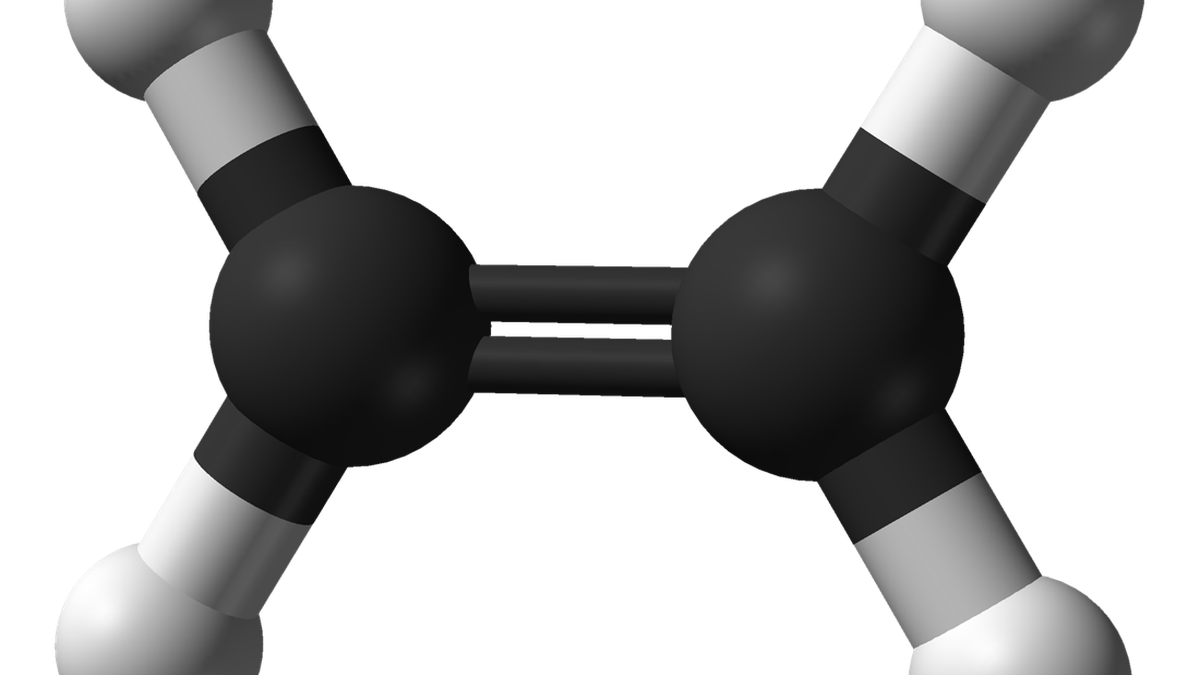

When a videogame wants to show a scene, it sends the GPU a list of objects described using triangles (most 3D models are broken down into triangles). The GPU then runs a sequence called a rendering pipeline, consisting of four steps.

(i) Vertex processing: The GPU first processes the vertices of each triangle to figure out where they should appear on the screen. This uses maths with matrices (sort of like organised tables of numbers) to rotate objects, move them, and apply the camera’s perspective.

(ii) Rasterisation: After the GPU knows where each triangle lands on the screen, it fills in the triangle by deciding which pixels it covers. This step essentially converts the geometry of triangles into pixel candidates on the screen.

(iii) Fragment or pixel shading: For each pixel-like fragment, the GPU determines the final colour. It could look up a texture (e.g. an image wrapped on the object), calculate the amount of lighting based on the direction of a lamp or the sun, apply shadows, and add effects like reflections.

(iv) Writing to frame buffer: The finished pixel colours are written into an area of memory called the frame buffer. The display system reads the buffer and renders it on the screen.

Small computer programs called shaders perform the calculations required for these steps. The GPU runs the same shader code on many vertices or many pixels in parallel.

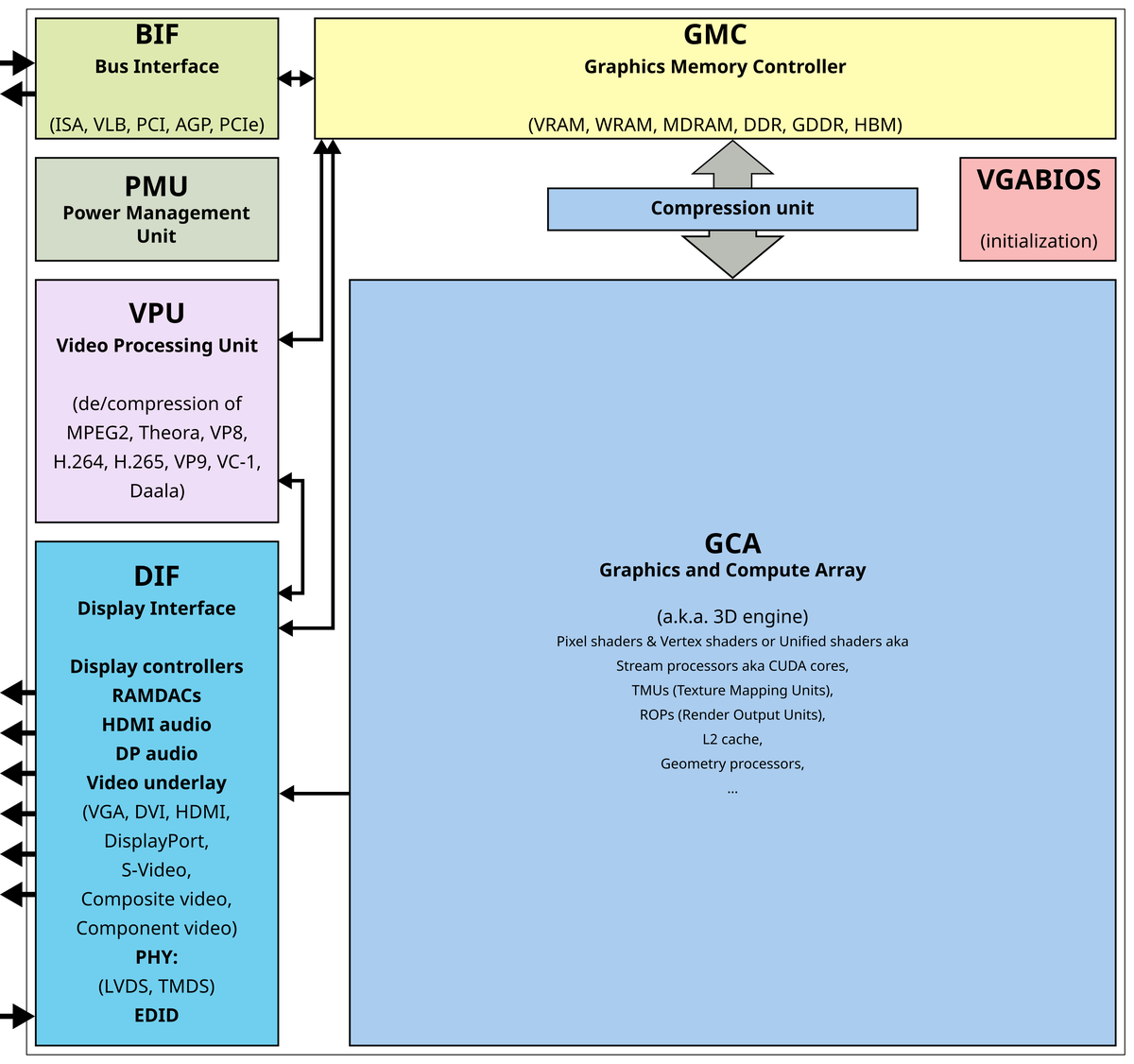

Effectively the GPU reads and writes very large amounts of data — including 3D models, textures, and the final image — quickly, which is why many GPUs have their own dedicated memory called VRAM, short for video RAM. VRAM is designed to have high bandwidth, meaning it can move a lot of data in and out per second. Still, to avoid having to fetch the same data, the GPU also contains smaller, faster memory in the form of caches and arrangements for shared memory, with the goal of keeping memory access from becoming a bottleneck.

A mock diagram of a GPU as found in graphics cards.

| Photo Credit:

Public domain

Many tasks outside graphics also involve performing the same type of calculation on large arrays of numbers, including machine learning, image processing, and in simulations (e.g. computer models that simulate rainfall).

Where is the GPU located?

A chip is a flat piece of silicon, called the die, with a fixed surface area measured in square mm.

In a computer, the GPU is not a separate layer that sits below the CPU; instead it is just another chip, or set of chips, mounted on the same motherboard or on a graphics card and wired to the CPU with a high-speed connection.

If your computer has a separate graphics card, the die holding the GPU will be under a flat metal heat sink in the middle of the card, surrounded by several VRAM chips. And the whole card will plug into the motherboard. Alternatively, if your laptop or smartphone has ‘integrated graphics’, it likely means the GPU and the CPU are on the same die.

This is common in modern systems-on-a-chip, which are basically packages containing different chip types that historically used to come in separate packages.

Are GPUs smaller than CPUs?

GPUs are not smaller than CPUs in the sense of using some fundamentally smaller kind of electronics. In fact, both use the same kind of silicon transistors made with similar fabrication nodes, e.g. the 3-5 nm class. GPUs differ in how they use the transistors, i.e. they have a different microarchitecture, including how many computing units there are, how they’re connected, how they run instructions, how they access memory, etc. (E.g. the ‘H’ in Nvidia H100 stands for the Hopper microarchitecture.)

CPU designers devote a lot of the die’s area to complex control logics, the cache ( auxiliary memory), and features that improve the chip’s performance and ability to make decisions faster. A GPU on the other hand will ‘spend’ more area on many repeating compute blocks and very wide data paths, plus the hardware required to support those blocks, such as memory controllers, register files, display controllers, sensors, on-chip networks, etc.

As a result, GPUs — especially the high-end ones — often have more total transistors than many CPUs, and they aren’t necessarily more densely packed per square mm. In fact, high-end GPUs are often very large. Some GPU packages also place dynamic RAM very close to the GPU die, connected using short wires with high bandwidth. Essentially, the architecture of components needs to ensure the GPU can transfer large volumes of data quickly.

Why do neural networks use GPUs?

Neural networks — mathematical models with multiple layers that learn patterns from data and make predictions — can run on CPUs or GPUs, but engineers prefer GPUs because the networks run many tasks in parallel and move a lot of data.

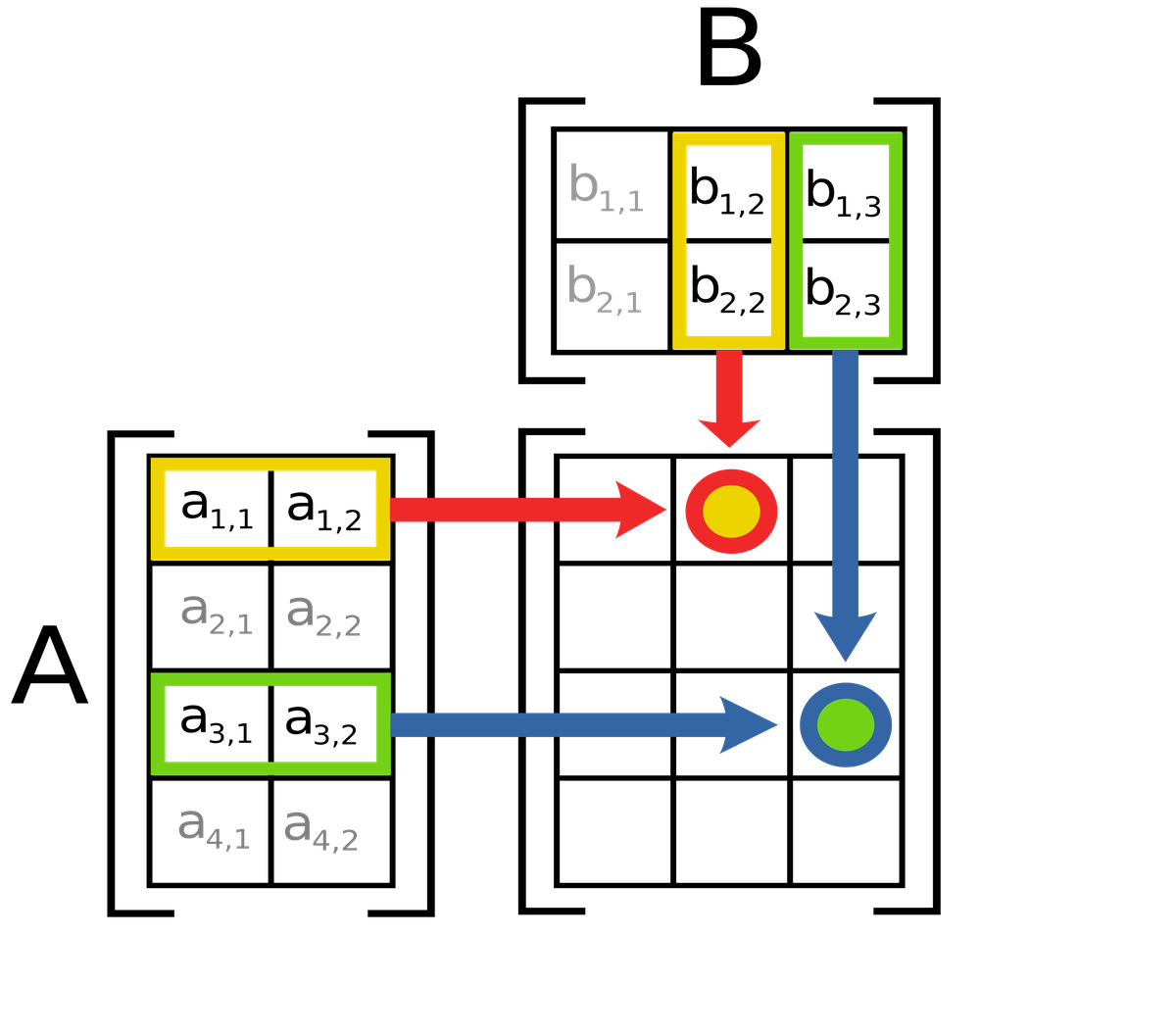

The maths of neural networks is in the form of matrix and tensor operations. Matrix operations are calculations on two-dimensional grids of numbers, like rows and columns; the numbers in each grid can represent various properties of a single object. The essential problem is to multiply two grids to get a new grid. Tensor operations are the same idea but use higher-dimensional grids, like 3D or 4D arrays. This is useful when the neural network is processing images, for instance, which have more properties of interest than, say, a sentence.

In matrix multiplication, the value of c12 (red-yellow circle) is equal to a11b12 + a12b22. Likewise, the value of c33 (blue-green circle) is equal to a31b13 + a32b23.

| Photo Credit:

Lakeworks (CC BY-SA)

A neural network repeatedly adds and multiplies matrices and tensors. Since it’s the same set of mathematical rules, just applied on different numbers, the thousands of cores of a GPU are perfect for the job.

Second, contemporary neural networks can have millions to billions of parameters. (A parameter is a learned weight or bias value inside the network.) So in addition to doing the maths, the network also has to be able to move data fast enough — and GPUs have very high memory bandwidth.

Many GPUs also include tensor cores, which are designed to multiply matrices extremely fast. For example, the NVIDIA H100 Tensor Core GPU can perform around 1.9 quadrillion operations per second of tensor operations called FP16/BF16.

In fact, Google developed chips called Tensor Processing Units (TPUs) to efficiently run the maths that neural networks require.

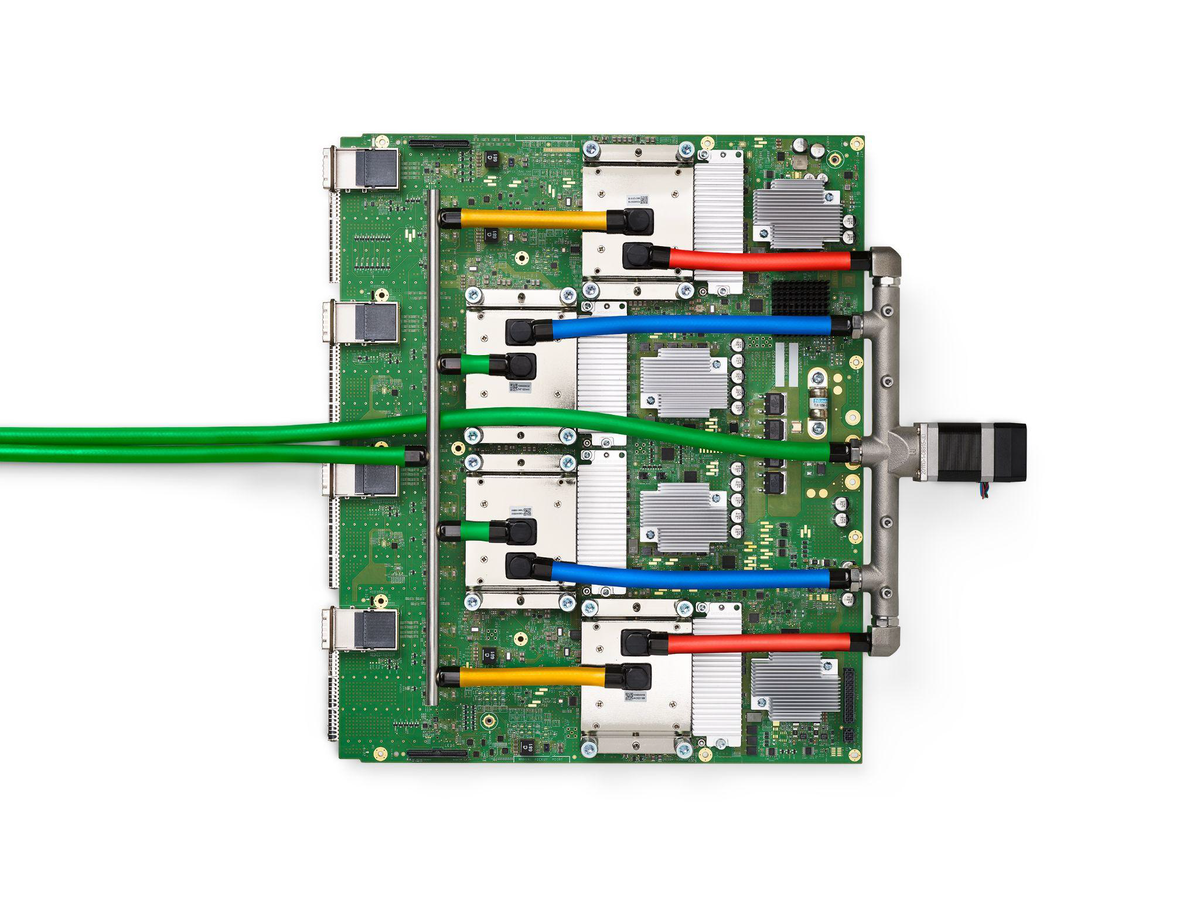

The green board everything is mounted on is the printed circuit board. The four flat, silver metal blocks arranged in a vertical column near the middle are liquid-cooled packages. The green hoses and the coloured tubes are coolant lines to and from the packages. Each package contains a TPU v4 chip surrounded by four high-bandwidth memory stacks. Four connectors dot the board’s left edge.

| Photo Credit:

arxiv:2304.01433

How much energy do GPUs consume?

Let’s use a hypothetical example where four GPUs are used to train a neural network to predict the risk of some disease for a person (based on age, BMI, blood markers, some history). Then the same network is put in use.

Each GPU is an Nvidia A100 PCIe, whose board power is around 250 W during training. The GPUs are nearly fully used during training. The training duration is 12 hours.

The energy consumed during training will be 12 kWh and during use, around 2 kWh (assuming only one GPU provides the inferences). The server will also consume power for its CPUs, RAM, storage, fans, and networking, and some power will be lost. It’s typical to add 30-60% of the GPU power for these needs. So the total consumption will be around 6 kWh/day for the network to run continuously.

That’s like running an AC for four to six hours at full compressor power, a water heater for around three hours or 60 small LED bulbs for 10 hours a day.

Does Nvidia have a monopoly on GPUs?

Nvidia technically doesn’t have a monopoly on GPUs; it enjoys a near-complete dominance in some markets and is a very strong market power in artificial intelligence (AI) computing platforms.

In discrete GPUs sold for use in personal computers, industry trackers have reported that Nvidia has roughly 90% market share at least, with AMD and Intel making up most of the rest). As for GPUs used in data centres, Nvidia’s position is strengthened by hardware performance and supply and the CUDA software ecosystem.

CUDA is Nvidia’s software platform to run general-purpose computation (like processing a signal or analysing data) on Nvidia GPUs. As a result, switching away from using Nvidia GPUs also means changing software, which companies don’t like to do. In fact, many buyers consider Nvidia GPUs running CUDA software to be the default platform for training and using neural networks at scale.

The legal definition of monopoly depends on whether a firm can control prices or exclude the competition and whether it maintains that power through unlawful conduct. This is why, for instance, European regulators have been investigating whether Nvidia uses its dominance to lock customers in, mainly by tying or discounting GPU prices when buyers also take Nvidia software or related components.

mukunth.v@thehindu.co.in