Mycelium to Miyawaki forests at India Art Fair 2026

Dumiduni Illangasinghe has always been “very serious about mushrooms” — just not in the way you’d imagine a 29-year-old to be. From the rain-washed fields of Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka where she grew up, to the forests of the Banaras Hindu University where she is currently studying, the artist has made the fungi her primary subject of observation. In the fragility and endurance of mycelial networks, she reads metaphysical lessons: specifically the Buddhist concept of “anitya” or impermanence.

At the India Art Fair 2026, where Illangasinghe is the first international artist in residence, she will present an installation titled Soft Armours, where she will turn broken glass bangles, traditionally considered harbingers of misfortune in South Asian societies, into delicate sculptures entwined with mycelial forms. “I want the viewer to see that broken bangles can also generate beauty, they can take on a new form and we can make new life with them,” she explains.

Dumiduni Illangasinghe

Soft Armours, where broken glass bangles transform into delicate sculptures entwined with mycelial forms

This philosophical engagement with ecological systems reflects a broader shift among emerging artists at the fair’s 17th edition (which, with 133 exhibitors from around the world, a star-studded speaker series, deeper engagement with design, and ever stronger IAF Parallel programmes, only gets larger in scope and strength each year).

According to director Jaya Asokan, this might be a sign of a generational reckoning. “What distinguishes these practices is their refusal of a romanticised return to ‘nature’,” she observes. “Instead, artists are engaging critically with stressed systems, agriculture, fungal networks, urban growth and extractive economies, through material experimentation and research-based approaches.” All reflective of the times and its very many conflicts.

Jaya Asokan, director, India Art Fair

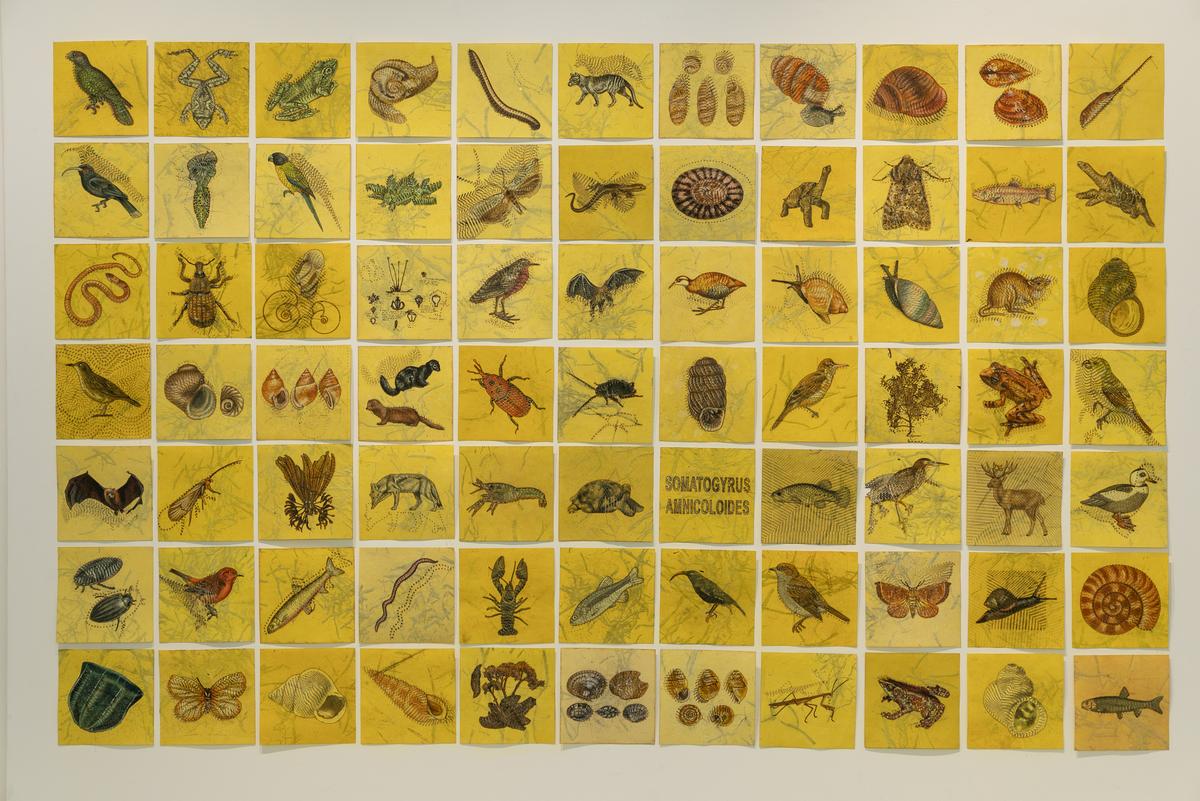

Armed with pesticides and questions

In Patiala-based artist Kulpreet Singh’s practice, the land itself becomes the medium. Singh’s outdoor art project, titled Extinction Archival, comprises approximately 1,200 drawings of endangered and extinct species. While the list of subjects has only been growing since 2022 (when he began by Googling the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species), the works themselves reflect the slow process of the farmer: stubble ash sandwiched with rice paper, which is then painted over, dipped in pesticide, and punctured with laser-cut dots. “It’s a commentary on all that is lost, all that is being polluted, and all that is stuck in between,” says Singh, 40.

Kulpreet Singh

Extinction Archival, with approximately 1,200 drawings of endangered and extinct species

At 25, multidisciplinary artist Sidhant Kumar’s work deliberately questions pastoral idealisations. “I’ve always wanted to challenge that idyllic definition of ‘landscape’ — the picture of greenery, clear water, bright sunlight, birds flying.” As a recipient of the Prameya Art Foundation’s DISCOVER 09 Award, Kumar will present his exhibit Studies from a Quiet Harvest — including a film, a statistical installation and photographs of him in performance in a cactus headgear — which emerged from long-term research at Ranhaula in Delhi, where migrant workers from Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Jharkhand cultivate vegetables on a share-cropping basis.

Sidhant Kumar

Studies from a Quiet Harvest (2025)

“It’s not like they can’t tell right from wrong,” Kumar observes, noting that the farmers end up using contaminated water from the nearby Najafgarh drain. “There is a lack of resources. This show is also about how capitalistic forces compel us to do those things that we must to only survive.”

In Mumbai, multidisciplinary artist Shreni moved on from architecture when she tired of pixel-perfect precision. Art offered a new language using familiar tools — and also of looking at all that grows in the cracks of mankind’s built habitats. At IAF, she will present Stand Here Forget, a large-scale generative AV installation that layers found sounds from across the city with code and algorithm. Inspired by her time in a forest near Bengaluru with scientists, here she uses ecology as an inspiration for the “system I’m developing” and highlight “the invisible structures that support us”. “I’m trying to recreate the feeling of just being within the city. I’m not proposing an answer, but want people to sit within a feeling, a contradiction,” she says. “My practice is always at the brink of something that is alien, yet familiar.”

Shreni

A work by Shreni

Stressing climate optimism

Elsewhere, artists forego critique for a more solutions-based approach. Colombo-based artist and permaculture enthusiast Raki Nikahetiya, 42, goes beyond observation. His Forest II, an installation supported by Max Estates, will be a Miyawaki-method pocket forest containing 200 native Delhi and Aravalli species, enclosed in structures built from construction waste metal — a literal refuge fashioned from the detritus of development. “I wanted to create a space where people can go, sit down and listen to these potential future sounds [of birds and bees and leaves rustling with the breeze] of this place,” he says.

Raki Nikahetiya

| Photo Credit:

Laurent Ziegle

The installation will eventually be replanted at a permanent Delhi location, sequestering carbon for decades while providing a habitat for birds, pollinators and soil fungi. Nikahetiya, who has been cultivating a permaculture forest in Sri Lanka, frames the work through what he calls “climate optimism”. “There’s a lot of anxiety with climate change, which is absolutely accurate, but there are potential ways of overcoming that.”

Forest II, a Miyawaki-method pocket forest

This impulse towards making something regenerative from what remains animates Tara Lal’s Aranyani Pavilion at Sunder Nursery as well (an IAF Parallel event). It is inspired by the sacred groves she has witnessed around India and the world. Merging ecology with public art through a bamboo structure clad with the invasive lantana camara wood, the pavilion illustrates the architectural possibilities of ecological liabilities. Atop the structure grow native and naturalised plants, including elaichi, jasmine and Ashoka trees. Within it, conversation around ecology and culture will flow for about 10 days, including a talk by environmental activist Vandana Shiva, before the entire pavilion moves to the Rajkumari Ratnavati Girls School outside Jaisalmer. “Instead of [the climate crisis] being something that pulls us down, we want to remind people of the emotional connection to our land,” Lal, 47, explains.

Tara Lal

Aranyani Pavilion at Sunder Nursery

Asokan notes that in these works, “ecology is framed as a physical network, one shaped by care, consideration, memory and resilience. Rather than simply pointing to collapse, these artists foreground adaptation, coexistence and alternative ecological futures, speaking from within complexity rather than distance”.

With natural life at its centre

As part of the IAF Young Collectors’ Programme (YCP) exhibit Omens Organisms Objects Order, Delhi-based artist Deepak Kumar’s, 32, contribution takes an anti-institutional approach, building what exhibit curator and YCP director Wribhu Borphukon describes as “a micro museum” of natural history modelled on roadside stalls, housing sculptures and drawings of flora and fauna that address how urbanisation pushes away natural life. Palghar-origin artist Gaurav Tumbada, meanwhile, will don a tiger head or “Waghoba” mask (the Adivasi community’s guardian) and present a contemporary interpretation of traditional dances from his region to address issues such as land acquisition, industrialisation and the vanishing of Warli art.

Deepak Kumar working on his piece Lost Native

YCP director Wribhu Borphukon

Borphukon identifies one key aspect that distinguishes younger artists’ ecological practices from earlier generations. “The lived experience is informing the contexts that they’re talking about,” he notes. “Having artistic responses to our preoccupations on multiple registers is important — you go from critique to soft activism to alternatives. Doing this across the spectrum is important.”

Art of resistance

Even though the primary purpose of IAF is to present a marketplace and a meeting point, Asokan has seen how larger shifts in the world have impacted artistic produce in the last decade. “There has been a marked shift towards materiality and questions of identity, belonging and labour, often articulated through mixed-media and interdisciplinary practices,” she says.

In response to AI and machine-led production, she’s seen “artists and curators returning to hand-made processes, foregrounding craft, familiarity and intention”. Galleries too are “taking greater curatorial risks, presenting research-driven and experimental practices rather than purely market-led selections”.

This observation resonates when you listen to Singh talk about the same “seva bhaav” he brings to his practice. Or when you listen to Kumar talk about understanding his purpose as an artist, while still studying in Vadodara. “My job as an artist is about community building, and it rests in resistance,” he reflects. “All I can try to do is arrest its speed [the end of nature as we know it] a little by spreading awareness.”

India Art Fair will take place from February 5-8 at NSIC Exhibition Grounds, New Delhi.

The Mumbai-based independent journalist writes on culture, lifestyle and technology.