India’s defence budget: A case for higher allocation

It is usual for defence allocation to rise sharply in the Budget that follows a security challenge. It has been the case this year too, in the shadow of Operation Sindoor.

The overall increase was more than 15% over the previous year (₹6.81 lakh crore to ₹7.84 lakh crore), with the capital outlay surging by 22% (₹1.80 lakh crore to ₹2.19 lakh crore). It may also look daunting that the defence budget has grown in the present century (2000-01 to 2026-27) by a hefty 1,240% (from nearly ₹0.59 lakh crore).

Union Budget 2026-27 documents

India’s defence expenditure since 1960 to 2024, as a percentage of its GDP, had averaged nearly 3% (World Bank data), and to many, that is impressive. It is not.

In the context of India’s rapidly evolving security requirements, its defence budget is middling. Our security outlays must be assessed in the context of the resources committed by nations that pose a threat to India, rather than in isolation.

Even the U.K., which has a strong military and is umbilically tied to U.S. security architecture, through NATO and a “special relationship”, spent nearly 4% of its GDP on defence during the same period (1960-24). The comparative figure for even the world’s preeminent power, the U.S., was 5.3%.

India’s unfriendly neighbour Pakistan, with which it has fought four major wars, has spent nearly 5%.

China, which is a greater threat to India, is in a different league altogether. It dwarfs India’s defence outlays. For 35 years up to 2024, its defence budget as a percentage of GDP, as assessed by the World Bank, averaged only 1.8%, though in reality, it was much higher, with estimates varying widely.

While China officially announced a defence budget of $246 billion in 2025, the overwhelming opinion is that it was much higher. Employing the midpoint of the US Department of Defense’s estimated range of how much higher the budget is, it would be $406 billion. Dan Sullivan, a U.S. Senator in 2023, citing government sources, assessed it was $700 billion. The Heritage Foundation estimated that in 2017, the Chinese budget was 87% of that of the U.S. It implied that in that year, China’s defence budget was $562 billion, as opposed to $647 billion for the U.S., and $68 billion for India.

To maintain a strong military, India has to spend more on defence, taking the budget to at least 5% of its GDP in the short to medium term and 6% to 7% in the long term. A credible deterrence against an increasingly aggressive China cannot be built on hopes.

Critics would argue that India does not have the capacity to absorb more defence budget. Without overhauling the existing system, it may be true as we are stuck in a stasis, crippled by a paralysis by analysis. How else can we describe the surfacing of the submarine project (P-75) after some two and a half decades of deciding that we needed a new series?

China, which did not even have an aircraft carrier when India operated one for decades, is expected to have nine by 2035. It today boasts that its latest carrier, Fujian, has an electromagnetic catapult which is only seen on the U.S.’s largest and latest carrier USS Gerald R Ford (commissioned 2017).

India’s first indigenous aircraft carrier took nearly 20 years to go from the planning to commissioning stage. We have not ordered the second so far, mainly on account of budgetary constraints.

A much larger budget with innovative strategies is required to attain a credible defence capability and build its domestic military industrial complex. Some progress has been made in this direction, but in the larger scheme of things, they do not add much. The irony is that we cannot even indigenously build large platforms today, save for a few, for which several critical systems are still imported.

We must grab the opportunities that come our way for important domestic production of sophisticated platforms, clearly understanding that India cannot become a strong military power by reinventing the wheels of technology of different systems, fearing a technology denial regime pervading the defence sector.

Defence capability is evolutionary and cannot be leapfrogged, unless through absorption of technology through collaborate ventures. Alternatively, or in parallel, it has to be built through reverse engineering and employing clandestine methods, routes that China has perfected — their J-11 fighter was modelled on Su-27, J-15 on Su-33, and HQ-9 air defence system on the S-300.

We need to unleash the power of our increasingly capable private sector. A larger defence budget would help forge collaborate ventures with private companies, with liberal government funding of critical projects. Such JVs could also survey the international landscape for collaborative ventures. The government must facilitate access to foreign companies and the private sector must negotiate with few constraints.

It is also utterly disappointing that we have not been able to take advantage of our close relations with either the Soviet Union or its successor, Russia, to develop our defence manufacturing capability. For instance, we did not actively pursue the goal of building nuclear submarines with Russian collaboration in India, soon after Akula-II lease contract was signed in 2004. It was a time when Komsomolsk-on-Amur shipyard, where it was built, was struggling for orders. Budget constraints were a dampener.

China exploited the opportunity and inundated the yard with its engineers whose targeted goal was to learn as much as possible about submarine-building on the back of the order for some conventional submarines they had placed on the yard. In contrast, India’s budgetary constraints prevented the deployment of staff, which was barely enough to take care of its immediate needs, when any technical manpower deployed at the yard could have had far greater access than China’s.

The opportunities that have opened up for the indigenous production of Su-57 fighter jets can be a vehicle for India to develop its aircraft-building capability. We should embrace the opportunity as we did in the early 1960s, when India produced the Mig-21 aircraft in collaboration with the Soviet Union. But we failed to follow the collaboration with the later versions. If we proceed with the Su-57 project, we would have access to a sophisticated supply chain and develop indigenous capability.

That collaborative ventures can succeed is exemplified by the success of BrahMos. Today, the time is right to negotiate with Russia to make India a production centre for defence wares to cater to nations that seek an alternate source of weapons to Western wares. Joint production of the S-400 defence systems could be a great opportunity. Once they are produced in India, we would be able to undertake research in collaboration with Russia and subsequently commit additional resources to undertake upgradation on our own. The attainment of steel-making capabilities after the establishment of the Bhilai and Bokaro steel plants should encourage us to take this route.

Streamlining the Ministry of Defence, adoption of unconventional methods of gaining technology, and forging collaborations — all without the constraint of funding — are the only ways to make India a strong nation.

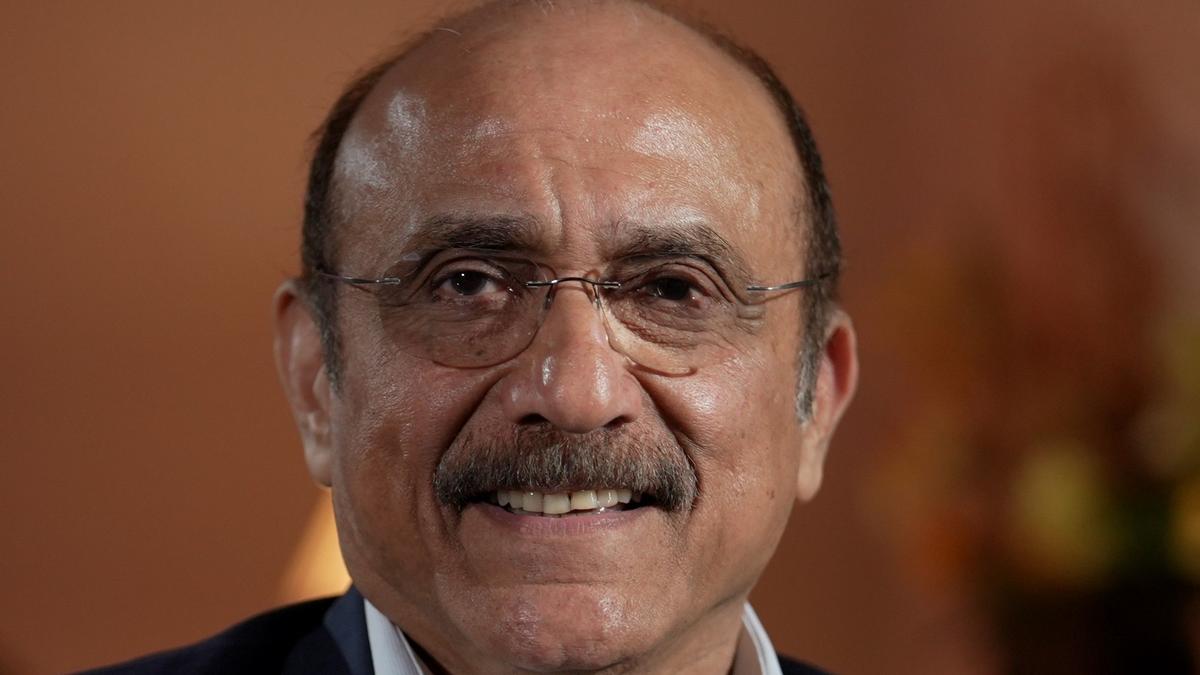

(The writer is former Civil Servant—held key position in the Ministries of Defence & Finance & Author of Ratan Tata: A Life)