At the last frontier of thought: will AI kill creativity?

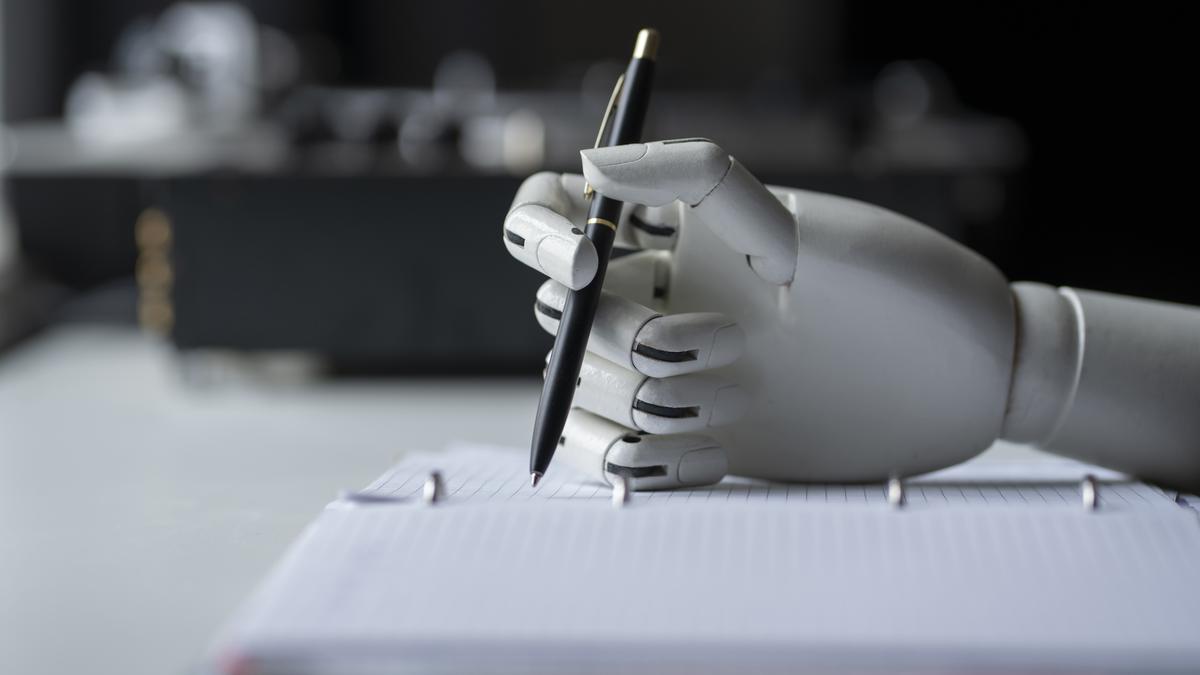

There was a time, not very long ago, when schools believed that the purpose of education was not merely to align it with narrowly defined employability outcomes, but to nurture thinking human beings. In my own schooldays, we were instructed to write an essay every third day, two uninterrupted hours of wrestling with ideas, not copying, not cramming, not downloading, but thinking on paper. Weekends were reserved for reading a novel or a play, and Mondays for speaking about it in our own words. This disciplined encounter with language and thought was the underpinning of intellectual upbringing. Today, that foundation has begun to crack.

The arrival of artificial intelligence (AI) has produced a fallacy that writing is a product rather than an existential act of human understanding and interpretative imagination. Increasingly, students, professionals, and even scholars have begun outsourcing their cognitive labour not because they lack intelligence but because the cult of speed and metric-driven performance has supplanted the pursuit of genuine thought. The digital age has indeed made access to information effortless, but access without engagement creates only the illusion of knowledge, a negligible gesture of cognition.

The writing self

It is therefore heartening to note recent developments in countries such as Denmark, where schools have begun to actively restrict the use of mobile phones, laptops, and digital devices, consciously returning education to traditional modes of learning.

Across human history, each generation has generally advanced cognitively and creatively beyond the previous one. Yet ours may be the first generation at risk of intellectual regression. Those of us educated before the digital deluge learned to wrestle with difficult questions and to research without instant answers at the touch of a button. As a research scholar, I learned to frame my own questions, search for material in physical libraries, and construct my own bibliographies rather than rely on ready-made data. I remember locating a single article in the National Library in Calcutta that led me to the critical works on Evelyn Waugh, eventually made available at New York University, material otherwise unavailable in India. This process, driven entirely by individual initiative, inevitably opened up unexpected and critically valuable avenues of reading, thereby cultivating curiosity, judgment, and creative thought, precisely the cognitive skills that risk being diminished when knowledge is reduced to instant retrieval rather than hard-won understanding. Unfortunately, the consequence is cognitive atrophy, and the striking paradox of AI’s promise of limitless access to knowledge pitted against genuine learning, which increasingly requires deliberate withdrawal from it.

For instance, the uncritical infusion of AI into scientific research has begun to corrode the very norms that once sustained scholarly credibility. Over the last two years, the volume of papers submitted to journals has exploded, not because of the emergence of authentic intellectual breakthroughs, but because AI systems can now rapidly generate texts that mimic scientific discourse. Reviewers with domain expertise increasingly report “phantom citations” that do not exist, or are misattributed, or only loosely related to the essence of the paper. These often slip through peer review undetected. The rapid inflation of output, consequently, has overwhelmed already strained editorial systems, making rigorous review unusually difficult.

AI-generated papers, containing subtle errors or fabricated sources, enter reputable journals and are then absorbed into training data and future research, thereby swelling misinformation. Meanwhile, careful, original researchers are eclipsed by sheer volume. In scientific disciplines, where inaccuracies can yield tangible and even risky outcomes, the dilution of verification processes, clear lines of responsibility, and intellectual honesty represents not merely a serious problem in how research is done, but a profound ethical concern.

Scholarly erosion

Yet AI is not the villain. In the right hands, it can expand access to knowledge and free human beings from intellectual drudgery so that the mind may turn to a richer form of creativity. When wielded intelligently, AI can operate as a powerful complement to human intelligence. fostering a mutual reciprocity that unlocks novel perspectives and redefines the frontiers of knowledge.

A recent claim by an AI enthusiast suggested that the “hallucinations” of large language models (LLMs) or their tendency to invent details, prove their humanity, and that such improvisation is akin to human imagination. The sentiment is whimsical but dangerously misguided. A metaphor emerging from a human being is shaped by memory, longing, pain and curiosity, the expression indeed of a lived experience. Clearly, when an LLM fabricates details, it is not imagining; it is predicting. Reducing imagination to probability, therefore, strips humanity of its essence, rendering it mechanical. The danger is not that AI is becoming human. The danger is that our definition of humanity is shrinking to resemble the logic of AI.

The death of language, therefore, is the death of democracy. Language is, more than a vehicle of communication, the means by which individuals articulate emotion, fear, dissent, hope and conviction. To lose the capacity to inhabit one’s own language is to yield to a structure of linguistic dispossession in which the capacity for free thought and expression is entirely eclipsed. It is well established that AI-driven propaganda already produces misinformation at an unprecedented scale; deepfakes manufacture heroes and villains in minutes; algorithmic precision enables political messaging to target the exact emotional and psychological susceptibilities of individuals. Consequently, very little resistance is possible from an electorate that has stopped thinking critically. They stand disarmed even before the battle commences.

Language and democracy

Moreover, the university has become the new battleground. Across the world, the humanities are being treated as expendable, sacrificed at the altar of an ideological script that identifies progress exclusively with STEM and market efficiency. The university, rather than being a sanctuary for critical thought, is being remodelled into a corporate skills factory. The vitality of language, the humanities, and democracy is inextricably linked. As language falters, the humanities decline, and democracy suffers in a generation that no longer reads books, no longer writes essays and no longer engages in the inner argument that creates conscience and critical thinking. In such an environment, language stands stripped of its oppositional power. AI, like every technology in history, would reflect the worldview of those who design and deploy it. If steered by corporate monopolies, it will accelerate hyper-consumption; if governed by authoritarian states, it will enable behavioural control; if animated by a market that values efficiency over imagination, it will produce a civilisation that mistrusts ambiguity, slowness and inwardness. It is not AI that threatens creativity because it thinks too much; it threatens creativity because it allows us to think less.

Therefore, universities must safeguard the humanities as the bedrock of critical thought, rather than treating them as ornamental indulgences. Democratic systems, in turn, must protect not only the freedom of speech and the intellectual labour of independent inquiry. AI can be taken as a valuable adjunct to human creativity, augmenting our capacity for insight and innovation, rather than usurping it.

At its core, the creative crisis we face is not a function of technological limitations, but a reflection of a deeper deficit in intellectual courage and imaginative tenacity. We have to come to grips with the fact that it is easier to copy-paste than to confront the mute page and wrestle a fragile thought into existence.

History instructs us that the edifice of civilisation has enduringly rested upon the shoulders of those who eschewed expediency in favour of rigour. If AI is to function as a complement to humanity, it must be steered toward the cultivation of imagination and language unfettered by the spectre of mechanical domination. The apprehension of diminishing our humanity must always linger at the margins of our consciousness. For the human essence is reaffirmed, as it has always been, in the primal act of creation with a child, bent over a desk, inscribing her own thoughts, fashioning meaning out of nothing. This, I recall, was the foundational lesson imparted by my daily essay-writing classes in school, a lesson whose wisdom manifests now, in this moment of technological transition.

Shelley Walia has taught Cultural Theory at Panjab University, Chandigarh