A century in the capital: How Delhi’s Parsis mark 100 years of community, faith and philanthropy

The Parsi community shares a deep-rooted relationship with Mumbai (then Bombay), where much of its history unfolded. Concentrated largely in older neighbourhoods such as Colaba, Parsis were among the city’s earliest builders and traders. “Several streets were named by Parsis, who were instrumental in shaping the city. There was a time when the community’s population ran into a few lakhs, with Bombay emerging as a natural hub because of its port,” says Adil Nargolwala, president of Delhi Parsi Anjuman (DPA).

Delhi, however, rarely figures in conversations about Parsi heritage — perhaps because of numbers. While Mumbai is home to nearly 40,000 to 50,000 Parsis, Delhi’s community stands at roughly 500. Yet the capital’s connection with the community is older than many realise.

Nargolwala notes that during Emperor Akbar’s reign, the Mughal court became aware of the Parsi community. Known for his curiosity about different faiths to create the Din-i-Ilahi, Akbar is believed to have met Meherji Rana of Navsari, the community’s chief priest. “He invited him to his courts in Delhi and Agra and granted a royal charter of several hundred acres of land,” he adds.

About 1,300 years ago, facing persecution in Persia (now Iran), the Parsis had migrated in order to protect both themselves and their faith. Their journey eventually led them to settle across Gujarat, Karachi, and Bombay.

0 R

By the time Delhi was established as the capital — first under Shah Jahan and later consolidated during British rule — the Parsis were already present in India. While there is no formal documentation of their interactions with Delhi’s residents during this period, oral histories and community narratives suggest their presence and engagement in the city.

Over the years, several prominent Parsis made the capital their home, including Dr Sorabji Shroff, who founded Dr Shroff’s Charity Eye Hospital in 1914; eminent jurists Fali S Nariman and Soli Sorabjee; and Homai Vyarawalla, India’s first woman photojournalist.

“Things really opened up when the British began establishing Delhi as the capital. Earlier, the city was confined to Old Delhi — a walled settlement with multiple gates, each leading towards a different region,” says Nargolwala.

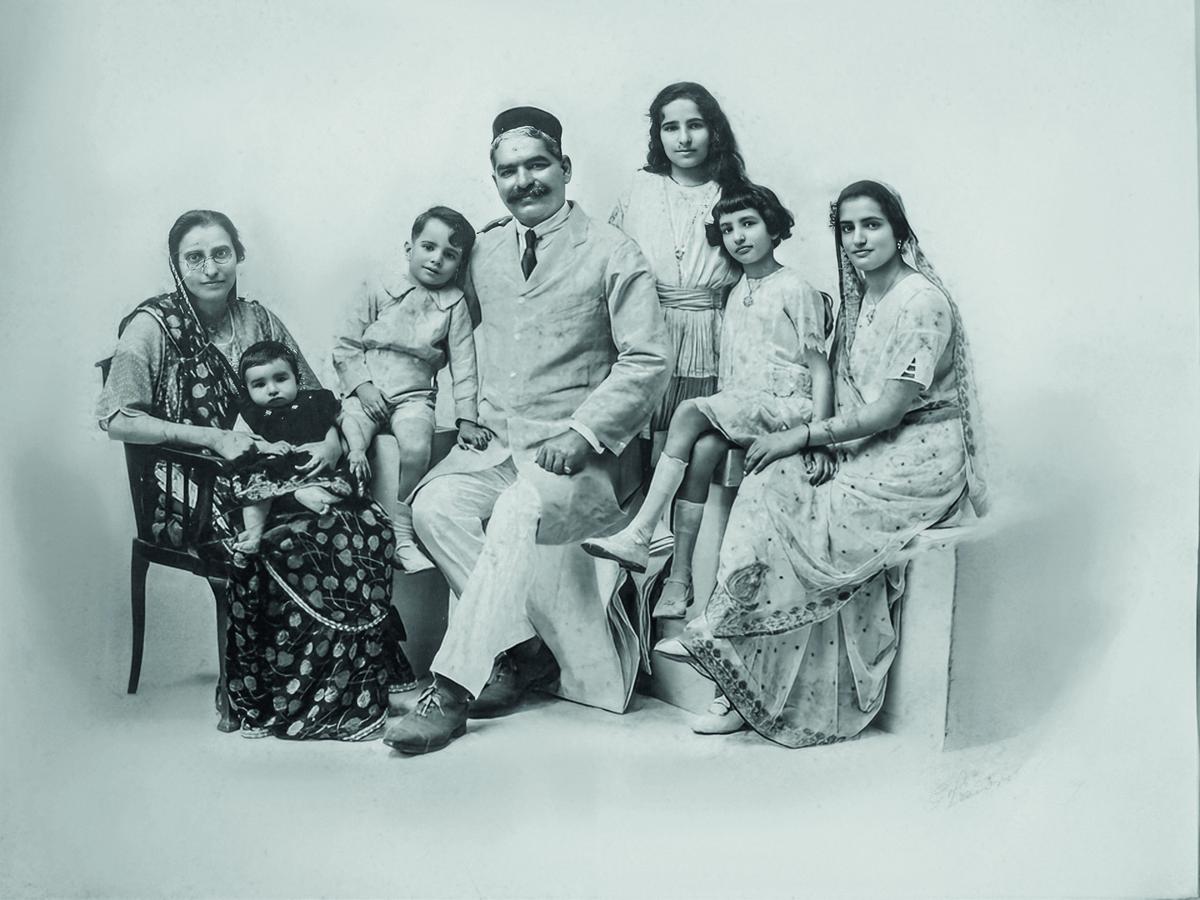

In the early 1800s, the Parsis in Delhi required land for burial, and the first plot allotted to them lay outside Delhi Gate. Over time, this area expanded, and in 1925, the constitution of the DPA was formally drafted, with Nowrosji Kapadia as the first president. The community’s earliest structure — a dharamshala for travellers — came up in the 1930s.

“In the 1950s, a hall for the community’s social and cultural activities was constructed. This was followed in 1961 by the fire temple, the only one in Delhi and among the few functioning in North India,” says Nargolwala.

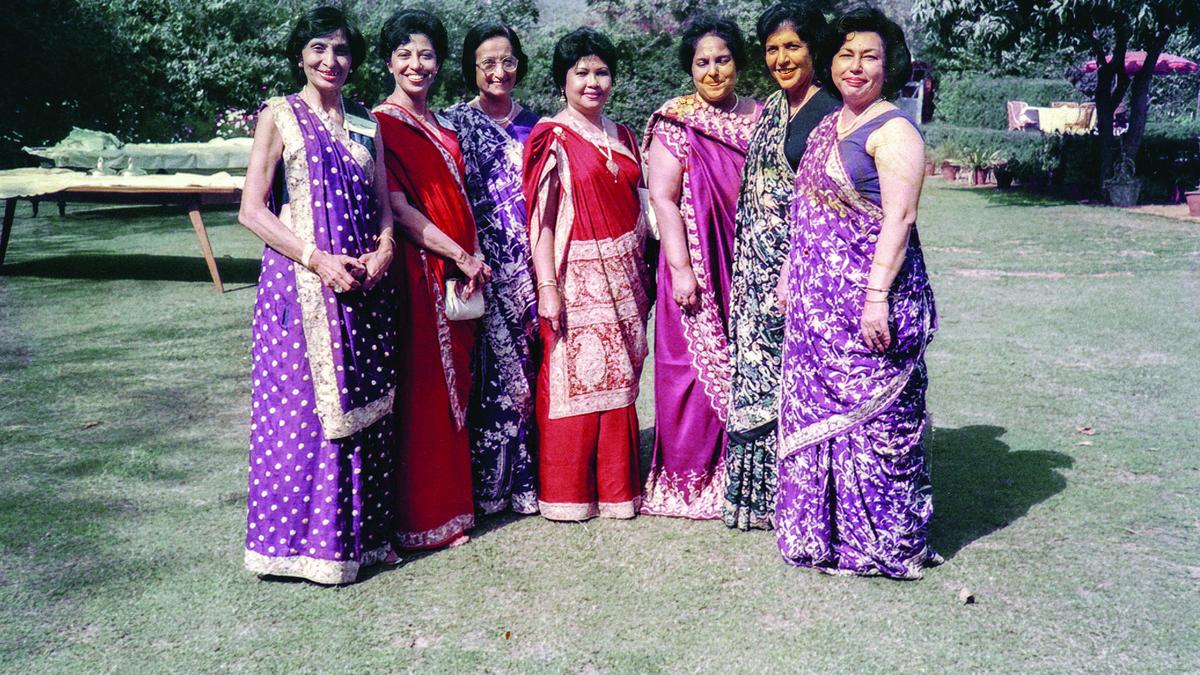

When Delhi was still a compact city, the DPA naturally became a focal point for festivals, weddings and cultural gatherings. Today, Delhi’s unruly traffic and the community’s dispersal across the city mean that members may not make it to the DPA as often. Yet, the centennial celebrations on December 13 and 14 drew a turnout of over 300 people.

The programme included a talk by Supreme Court Justice Jamshed Burjor Pardiwala, a felicitation ceremony honouring past and present community members, cultural performances, and a lavish spread of authentic Parsi cuisine by Surat-based A-One Parsi Food. The menu featured kolmi fry, chicken cutlet, dahi chicken, chicken pulao, bhaji dana, papeto gravy, patra nu paneer, sev and lagan nu custard.

“The fire temple also marked 64 years since its consecration and has recently been renovated,” he adds.

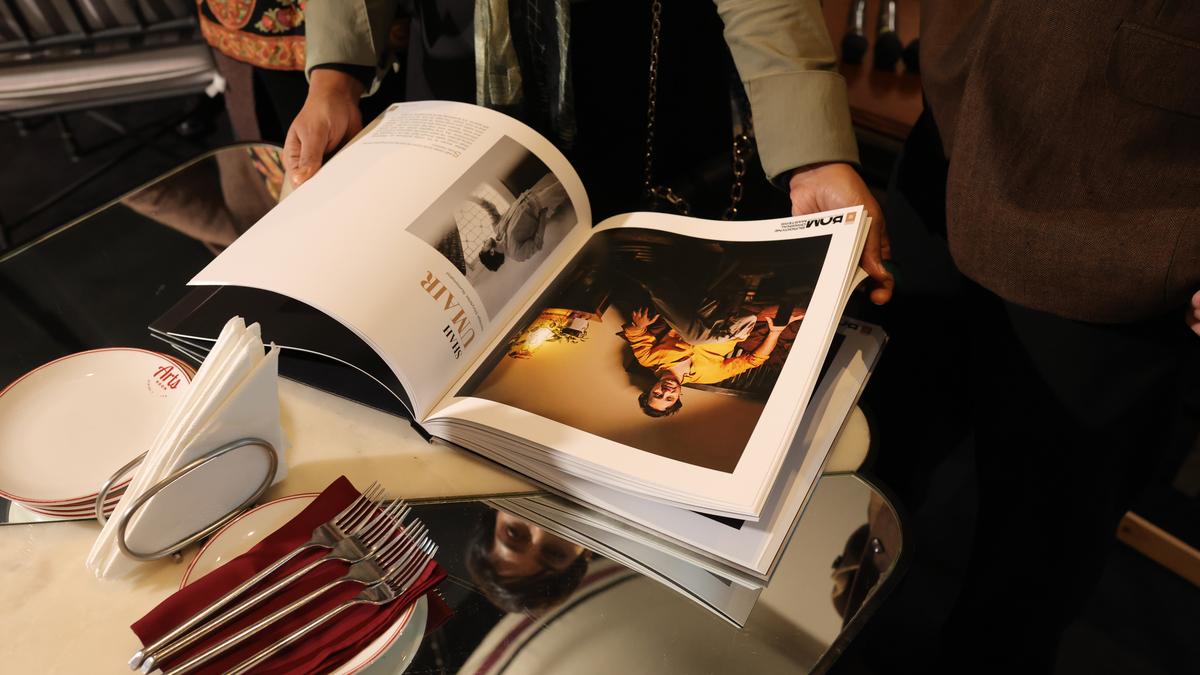

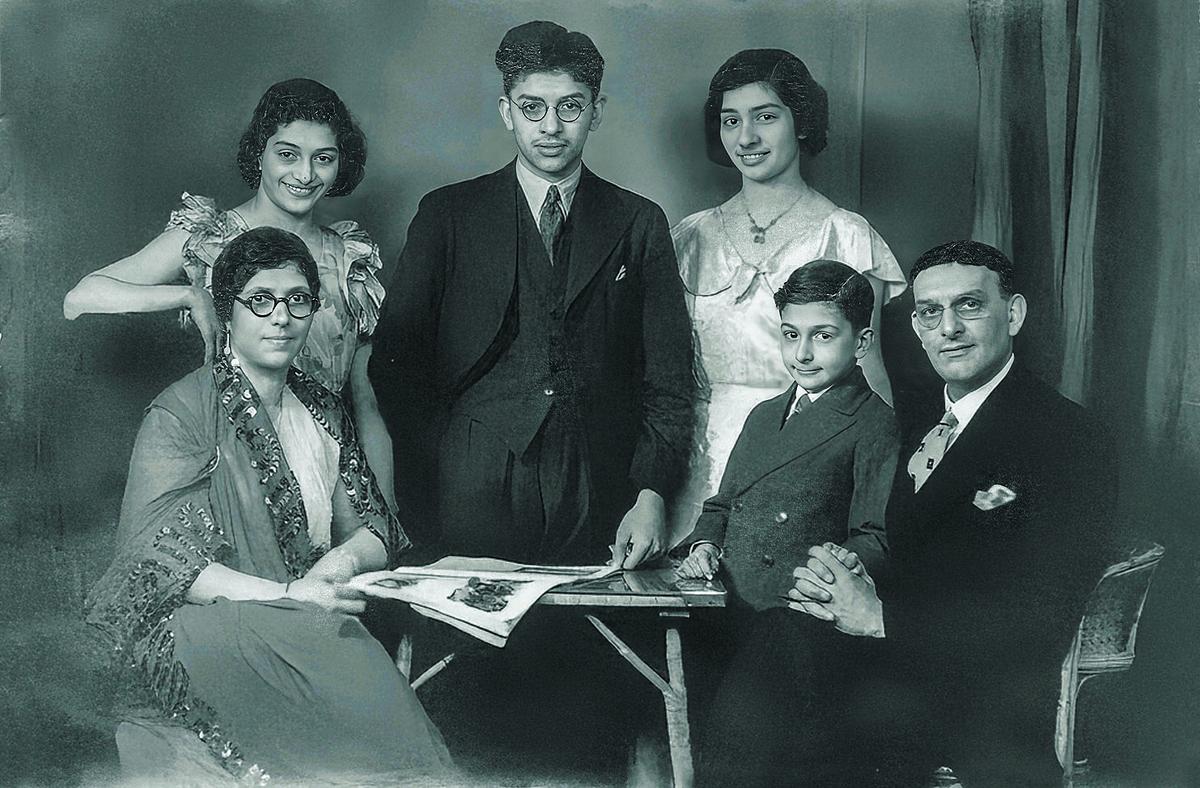

An exhibition of nearly 250 photographs has also been set up in the dharamshala, tracing the journey of the earliest Parsis who settled in Delhi to the present generation. From images of Akbar’s farman to Meherji Rana, to archival records of Parsis who have served the country in various capacities over the years, the exhibition will now remain on permanent display.

Beyond the centennial celebrations, the DPA marks Navroz, the Parsi New Year, every year. It also hosts smaller religious gatherings and commemorates milestones or achievements of notable community members, including events held in memory of its late president, General Adi Sethna. The Anjuman Hall, meanwhile, is open for all and has, over the years, hosted several non-Parsi events as well.

While preserving Parsi culture is vital, especially for a community that is both small and close-knit, its philanthropic ethos is equally defining. “Unlike larger communities that often focus outward, we believe in an inward approach,” explains Nargolwala. “We receive many appeals to support the elderly, cover health and medical expenses, and help young people with scholarships for higher education.”

He also points to Jiyo Parsi, an initiative aimed at addressing the community’s declining numbers. “With many couples marrying later, fertility can become a challenge. We support fertility clinics, so couples can receive proper guidance. These efforts are fully funded by the community. Our focus is to ensure that the community continues to grow.”

Published – January 27, 2026 02:07 pm IST