Beat the clock and crack the exam

Mock tests and previous years’ papers must be scrutinised with seriousness, not as optional add-ons.

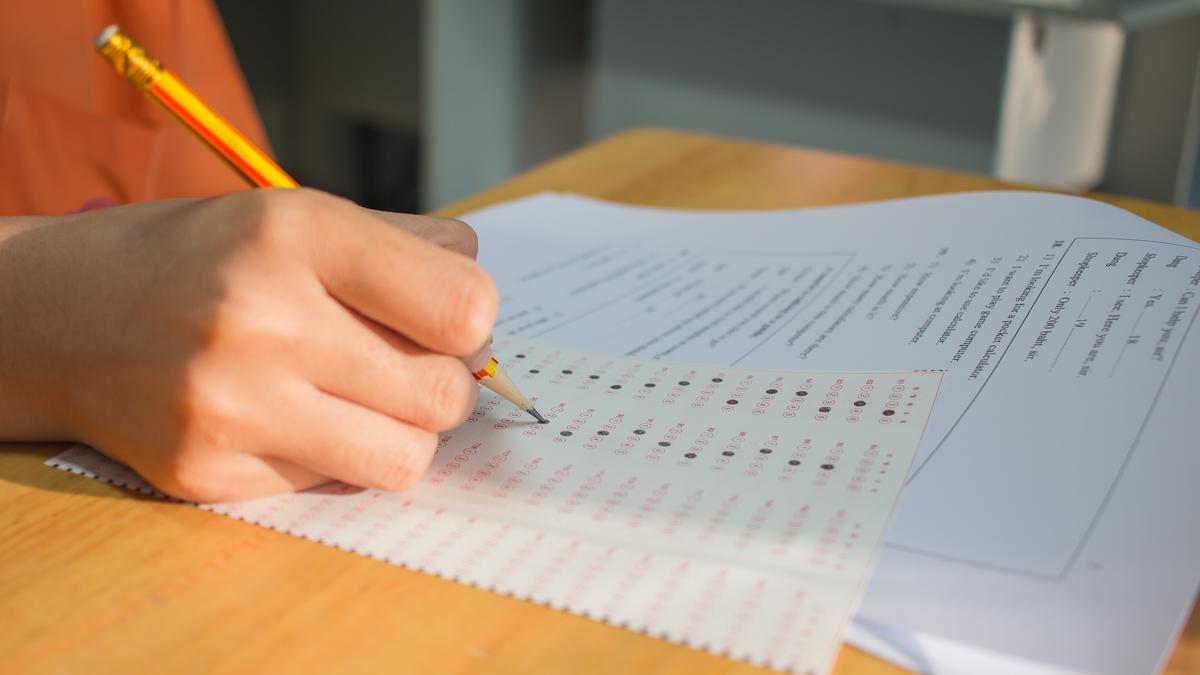

| Photo Credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto

In every examination, the true test is not merely whether a student can answer questions, but whether they can answer them within a fixed time. This distinction, often overlooked, is what separates good performances from great ones. Time-boundproficiency is a skill that demands deliberate practice, and the most reliable way to sharpen it is through weekly timed mock tests. Sitting down once or twice a week with past papers, following the exact marks-to-time ratio, and completing the entire paper without interruption gives students the closest simulation of the real exam environment. What follows may be the most crucial step: evaluating the paper with uncompromising honesty.

Every mistake in such practice tests falls into one of three categories. A knowledge gap, where the concept itself is not understood; an accuracy gap, where the student knows the concept but commits avoidable errors; and a speed gap, where answers are correct but too slow. Reducing these categories one by one dramatically improves exam readiness.

Mock tests and previous years’ papers must be scrutinised with seriousness, not as optional add-ons. These papers often reveal patterns that hardly change year after year. Once these patterns are understood, the next discipline is time allocation. Students should divide exam time in proportion to marks. For a 100-mark paper scheduled for 180 minutes, a 20-mark question must ideally receive one-fifth of the total time — around 36 minutes. In practice, easier questions naturally consume less time, giving students a buffer of roughly ten minutes for revision at the end.

Reflecting on school days, many students hesitate to ask questions in class, fearing judgement from peers. But questioning lies at the heart of learning. Teachers are almost always willing — even eager — to clarify doubts, provided the student demonstrates genuine curiosity. A motivated student rarely finds a teacher unwilling to meet them half way.

Daily revision is another non-negotiable habit. After returning from school, revising the day’s lessons helps seal concepts before they fade. Every student has a preferred rhythm: some are larks who study best during daylight hours, while others are night owls who find focus after sunset. The key is not conforming to someone else’s schedule but understanding one’s own.

Strategic preparation begins with the syllabus itself. Going through it line by line and categorising topics into three lists — “should know”, “must know”, and “could know” — creates a clear road map. Preparation must follow that exact order.

Quality study matters more than quantity. The 45–10 method offers a scientific approach: forty-five minutes of deep, distraction-free study followed by a ten-minute break. During these sessions, students should summarise concepts, explain them aloud as though teaching a class, or generate quick questions. Notes should be functional, not decorative — short headings, precise points, simple diagrams, a couple of examples, and a small formula box.

In the final week before the exam, students must resist the temptation to pick up entirely new topics. Instead, they should revise notes, practise past questions, and consolidate familiar concepts. On exam day, adequate sleep, punctuality, a quick five-minute scan of the paper, beginning with the easiest questions, and reserving ten minutes for revision can make all the difference.

Exams ultimately reward preparedness and discipline — but above all, they reward those who learn to race the clock.

advityanidhi14@gmail.com

Published – January 25, 2026 03:28 am IST