Union Budget 2026-27: Building on a tax gamble that did not pay off

One interesting thing about the Budget is that people usually do not do a reality check vis-a-vis the previous Budget because the current one takes centre stage. Since Budget 2026-27 is quite run of the mill, it will not be out of place to start with the last Budget.

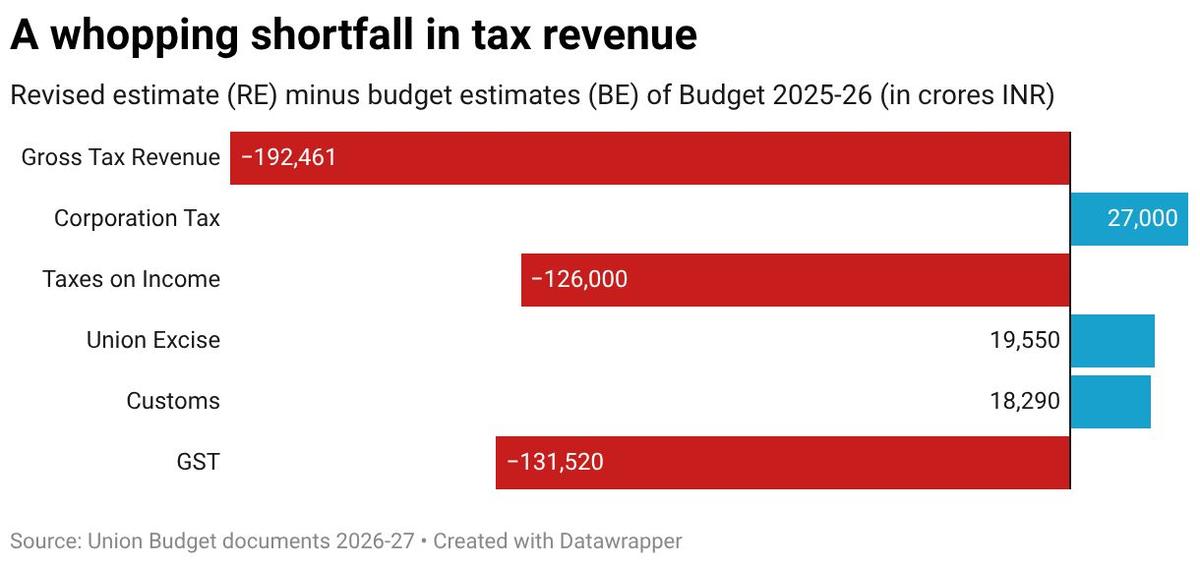

If there is one thing you would recall about Budget 2025-26, it was the big-ticket announcement of an unprecedented tax cut for the “middle class”. The government assumed that despite the tax cut, income tax revenues would go up because of higher compliance and rise in middle-class incomes. But did that happen?

Looking back

As we had argued last year in these columns, the tax gamble may not pay off and it has not. Income tax revenues have fallen woefully short of the estimated 14.38 lakh crore. In the Revised Estimate (RE), the collection is 13.12 lakh crore, so a shortfall of 1.26 lakh crore. Add to that a similar shortfall of 1.31 lakh crore in GST collections. But for a marginally better than expected performance from corporate tax, union and excise duties, the shortfall in the overall gross tax revenue would have been much higher than 1.92 lakh crore (tax part of the chart).

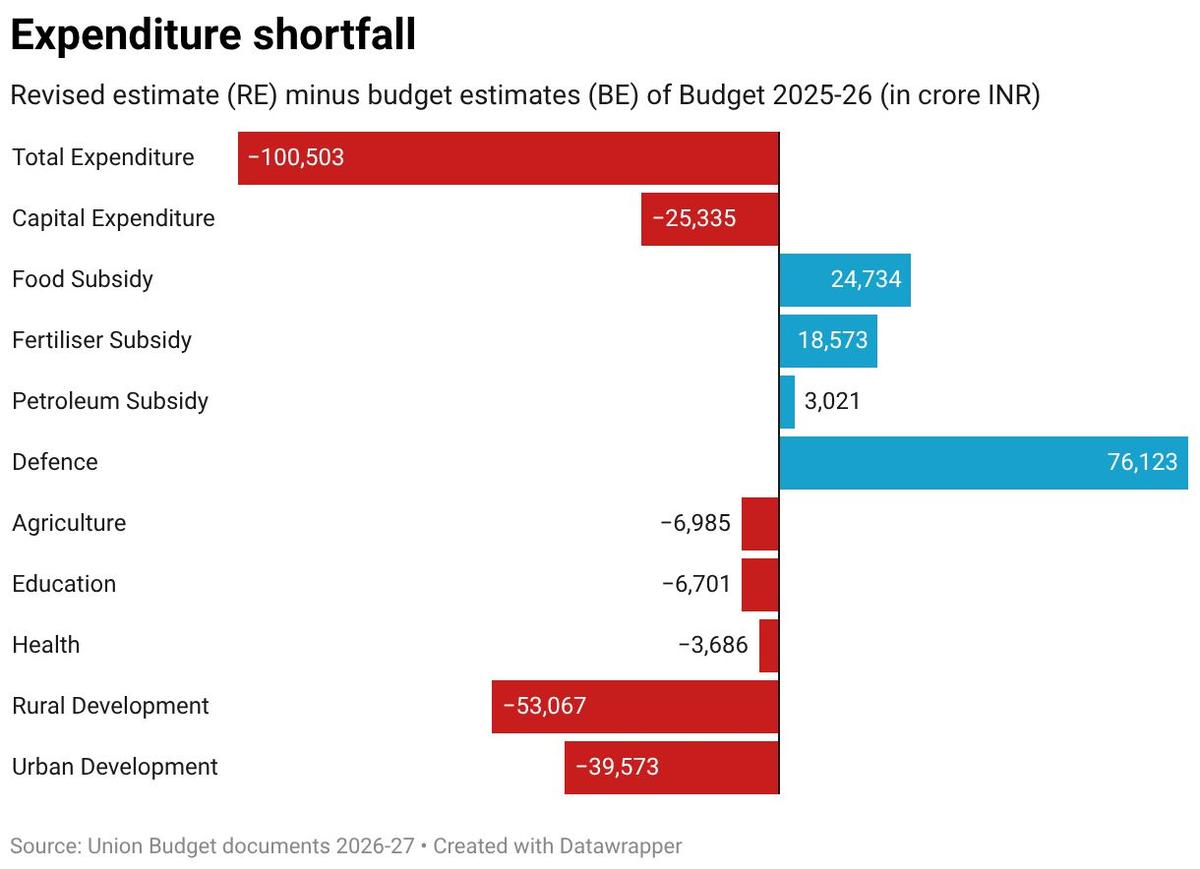

To be sure, this shortfall in itself could be dismissed as a mistake in expectations. But when expenditures are linked to tax collections (which they strictly are under the rules of fiscal deficit targets), the matter is far more serious. When spending is directly tied to revenue collections, a shortfall of this magnitude inevitably results in sharp expenditure cuts. Not surprisingly, there has almost been an across-the-board cut in expenditure (expenditure part of the chart). Even the much-touted capital expenditure (capex) saw a cut, as did agriculture, education, health, rural as well as urban development. A mistake in the government’s expectations cost the poor their income, their employment, their education and, their health.

Not for 2026

Budget 2026-27 needs to evaluated in light of this. This is going to be an uncertain year, both politically and economically. India is precariously placed between a current account surplus with the U.S. but a deficit with China. If its exports gets affected as a result of President Donald Trump’s tariff war, without its imports countering the fall, the external situation for India may actually worsen. The Economic Survey at least acknowledged this possibility, although with a low probability of 10%. In a fundamentally uncertain world that we currently find ourselves in, you don’t want to take refuge in probability theory.

The Budget seems to have taken this probability a little too literally. It has been planned as if we are still in 2025 and such a worsening of the external sector may not happen. If the external demand actually worsens, it is important for the government to focus on domestic demand as well, at least as plan B. A run-of-the-mill Budget like this one would have been fine in normal times but not this year. The focus remains on fiscal prudence, capex, supply-side measures for employment, and credit guarantees to MSMEs, much like the previous Budget or the ones before. Despite the same macroeconomic approach in earlier Budgets, employment numbers, particularly among the youth, have not been encouraging at all. Corporate investment has not been either. Should not the government have gone back to the drawing board if their existing strategies were not working? And yet what we got is more of the same. This lack of imagination comes from a blinkered vision of how the economy works. Supply-side measures work only when complemented with demand, not on their own.

Let us again take the case of public capex as a demand measure. All capex are not the same. Capex in agriculture or health or education is not the same as capex in highways. The first creates jobs along with boosting demand. Now in a world where you don’t pit one capex against the other, this would not have been an issue. But if capex in infrastructure comes at the cost of capex in the form of development expenditures, and that too in an economy where gainful employment is limited, there is a serious problem. We keep boasting about our demographic dividend, which is going to peak in 2030, but we have lost most of it already with a high unemployment rate among the youth. For women, particularly in the urban areas, it is even worse.

Missing targets

What could the Budget have done instead? First, it should have kept its hawkish fiscal stance in abeyance, especially for an uncertain year such as this. It should have prioritised employment intensive development expenditure, and welfare expenditure, which also have a multi-round demand generating capacity. And second, this was perhaps the year to take the pollution bull by the horn. People were on the streets of Delhi demanding action. For the first time, it became a political issue. We needed a war on pollution but it does not even find a mention, let alone allocation. It is an opportunity lost.

Rohit Azad teaches Economics at JNU; Indranil Chowdhury teaches Economics at PGDAV College, Delhi University

Published – February 02, 2026 12:48 am IST