Asia Society Arts Game Changer Awards | How CAMP is reworking the rules

At a time when the future increasingly feels like a repetition of the past, the idea of “game changing” demands scrutiny. On social media, comparisons between 2026 and 2016 circulate with uneasy familiarity: from resurgent authoritarianism to culture wars, and identity politics over visibility and speech. It is precisely this anxiety that gives the Asia Society Arts Game Changer Awards their urgency.

Instituted by Asia Society India, the awards were conceived to recognise practices that have shifted how art is made, circulated, and understood across South Asia. The award’s emphasis is deliberate: individual excellence, once the primary currency of cultural recognition, has revealed its limits in an increasingly unequal world shaped by infrastructure, technology, and access, necessitating collaboration across disciplines.

This year’s awardees underline that shift. The 2026 cohort includes Sri Lankan artist Hema Shironi, whose textile-based practice stitches together post-war memory, Tamil identity, and anti-colonial resistance; Kulpreet Singh, a Punjab-based farmer-artist whose soot drawings emerge directly from agrarian crisis and climate catastrophe; Raghu Rai, whose six-decade photographic archive has shaped how India remembers itself; and CAMP (Critical Art and Media Practices), whose work spans film, surveillance, and open digital archives.

Hema Shironi

One Loan is Taken to Settle Another IV (2023; hand mebroidery on printed fabric and cotton fabric)

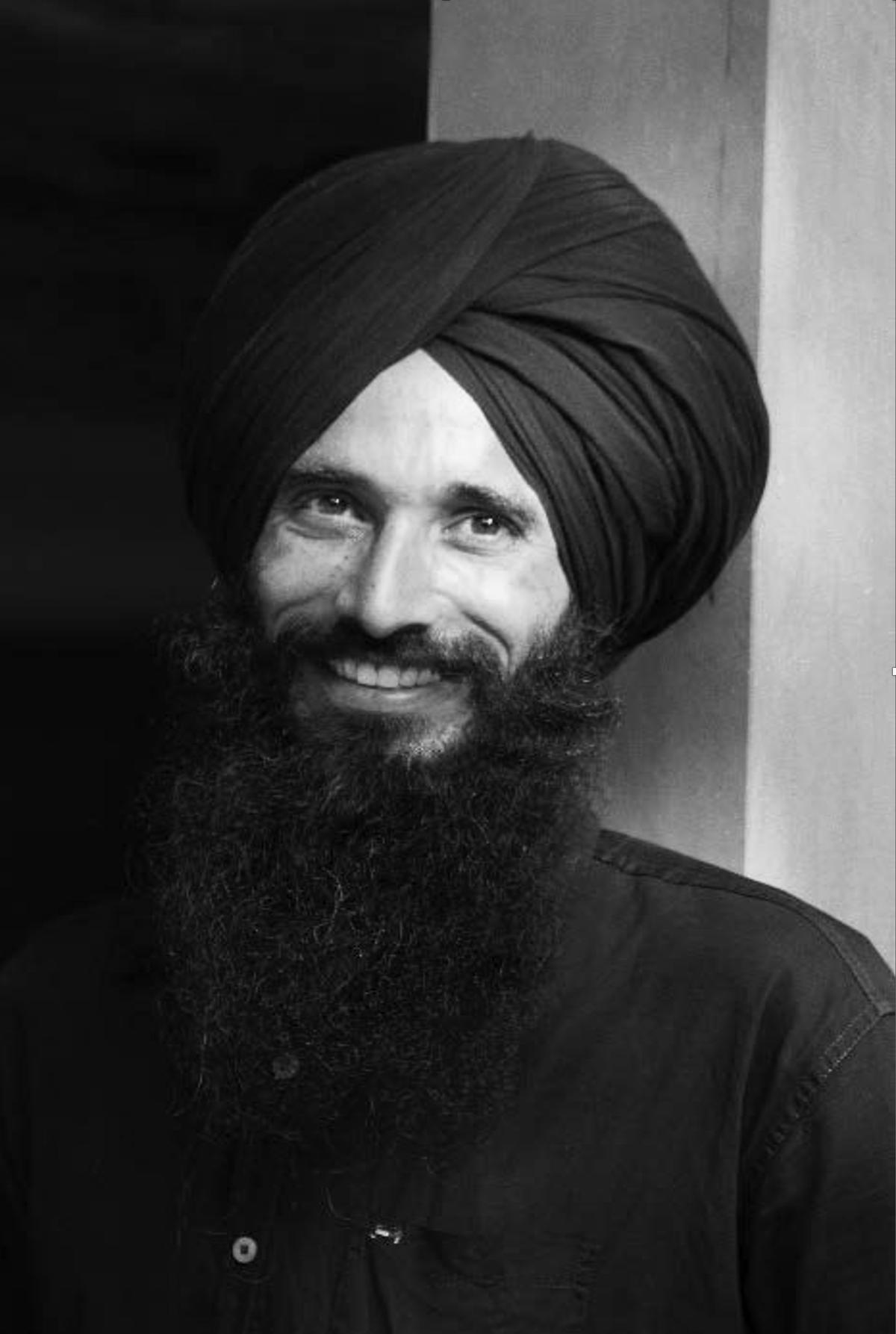

Kulpreet Singh

Indelible Black Marks (2022-24; cotton cloth, thread, stubble ash, and ash from wooden stoves at sites of farmerp rotests)

| Photo Credit:

Ashish Kumar

Raghu Rai

‘Art as something to inhabit’

Among them, what makes CAMP’s practice particularly fascinating is its irreverence for prescribed definitions of form, format, media, and art itself. Founded in Mumbai in 2007 by Shaina Anand and Ashok Sukumaran, the collaborative studio has spent nearly two decades working across moving-image practice, technological systems, pedagogy, and long-term public infrastructure. Their projects include Pad.ma, an open-access online archive of documentary footage, and Indiancine.ma, a collaboratively built database of Indian cinema that functions as both archive and research commons.

Clockwise from top left: Zinnia Ambapardiwala, Shaina Anand, Ashok Sukumaran, and Rohan Chavan

Neither platform operates as a neutral repository. As Anand puts it, “We said ‘infrastructure’ long before it became a word in art or anthropology. Within three months of starting CAMP, Pad.ma was launched, and it already brought together and belonged to a larger community than us.”

What distinguishes CAMP’s practice is not scale or novelty, but method. From the outset, they were responding to a specific set of conditions. In the mid-2000s, India’s contemporary art market was expanding rapidly, absorbing visibility and capital, while documentary filmmakers faced shrinking exhibition spaces, limited distribution, and increasing censorship. “We came from a time when the Internet felt like a forest. A place to hide, organise, to build autonomously. We also assumed airwaves, electricity as free media, as commons,” she explains.

CAMP’s A Photogenetic Line installation is a 100-foot-long branching sequence of cutouts, with original captions, from the photo archives of The Hindu.

CAMP emerged at this intersection with a clear proposition: if existing structures could not hold certain kinds of work, those structures had to be rethought or built anew. “Art wasn’t something to hang on a wall. It was something you could inhabit. Something that could exist inside systems — archives, cities, surveillance — rather than just represent them,” says Sukumaran.

Khirkeeyaan is a video installation where the neighbourhood TV was repurposed as conversation systems in a mashup of cable TV and early CCTV systems.

Shaping how images circulate

Central to CAMP’s thinking is a refusal to separate art from its conditions. Filmmaking, building archives, or intervening in surveillance systems are treated as artistic acts because they shape how images circulate and who gets to see them. “The work might take the form of filmmaking, or building an archive — but the method, the commitment, is art,” says Anand. This position also explains CAMP’s resistance to being framed as an “artist collective”. The term, they argue, often replicates the logic of individual authorship under a shared name. Instead, they treat collaboration as an active process that is negotiated, strategic, and often risky.

Country of the Sea is a cyanotype map based on CAMP’s five-year project with Gujarati sailors in the Western Indian Ocean, from Kuwait to Mombasa.

Working with CCTV operators in the U.K., Palestinian families filming their own neighbourhoods in East Jerusalem (Al Jaar Qabla al Daar), sailors documenting life across the Indian Ocean (From Gulf to Gulf to Gulf), or residents reading Mumbai’s skyline through poetry (Bombay Tilts Down), CAMP repeatedly asks: who controls the image, who benefits from access? “There are already millions of cameras in our cities. The artistic question isn’t whether to bring another one, but to use what’s already there to show something else,” says Sukumaran. By repurposing surveillance technologies, allowing cameras to observe neighbourhood life rather than guard private property, they interrupt the logic of the panopticon.

Bombay Tilts Down was filmed from a single-point location by a CCTV camera atop a 35-floor building.

A shared commitment

Their approach extends cautiously to newer technologies. Rather than embracing claims of inevitability around artificial intelligence, CAMP treats machine tools as situational: useful for translation, research, or archival labour when aligned with ethical intent, and resisted when they obscure accountability. “We don’t accept the current use of any technology as its final destiny,” notes Sukumaran.

In this light, the Asia Society awards function less as endorsement than as recognition of sustained risk. Placed alongside Shironi, Singh, and Rai, CAMP’s practice reveals a shared commitment: art that stays close to lived conditions rather than abstract trends. To “game change” art, then, is not to predict the future, but to refuse its repetition. In a moment when the past threatens to return intact, CAMP’s work insists on rebuilding the rules themselves.

Asia Society Arts Game Changer Awards will be presented on February 6 in New Delhi.

The essayist-educator writes on culture, and is founding editor of Proseterity — a literary arts magazine.

Published – January 30, 2026 11:49 am IST